Question: What is meant by not to “give ground to one’s desire.” I recognize the discussion of Antigone and that she stays with what she believes is right despite Creon’s decree.[1] Does giving ground to one’s desire mean not to give up on one’s desire despite the little other, so staying with the Big O? Does ‘giving ground’ mean ‘giving way’?

Answer: To respond to the last question first, to ‘give ground’ means to withdraw under attack, to retreat or to yield. Not to give ground to one’s desire is thus not to give up on what it is that desire is asking of one. Notice here that this is not ‘my desire’, i.e., my ego’s desire, but what desire is asking of me. Lacan points out that “while desire is the metonymy of the want-to-be (manque à être), the ego is the metonymy of desire” (Lacan 2002[1996]-a: p534[640]). Not to give ground to one’s desire is thus not to withdraw, retreat or yield in the face of what desire asks of one, but rather to embrace it in order to remain true to one’s manque à être in following the metonymy of desire.

But this ‘not giving ground’ is not so simple, because Lacan also points out that in seeking to do so, the subject always also betrays himself:

What I call “giving ground relative to one’s desire” is always accompanied in the destiny of the subject by some betrayal […] Either the subject betrays his own way, betrays himself, and the result is significant for him, or, more simply, he tolerates the fact that someone with whom he has more or less vowed to do something betrays his hope and doesn’t do for him what their pact entailed… Something is played out in betrayal if one tolerates it, if driven by the idea of the good – and by that I mean the good of the one who has just committed the act of betrayal – one gives ground to the point of giving up one’s own claims and says to oneself, “Well, if that’s how things are, we should abandon our position; neither of us is worth that much, and especially me, so we should just return to the common path.” (Lacan 1992 [1959-1960]: p321)[2]

What is challenging here is to distinguish between a ‘good’ defined by a big-O Other, for example by the Law, and desire in the sense of a being in relation to the lack of a big-O Other S(A-bar): “signifier of a lack in the Other, a lack inherent in the Other’s very function as the treasure trove of signifiers.” (Lacan 2002[1996]-c: p693[818]). In thinking this way, “there is no other good than that which may serve to pay the price for access to desire – given that desire is understood here, as we have defined it elsewhere, as the metonymy of our being.” (Lacan 1992 [1959-1960]: p321)[3]

In response to your first question, you make two kinds of error, therefore, in asking if “not to give up on one’s desire despite the little other” means “staying with the Big Other”. First, it identifies the relation to the Other’s lack () with the Other’s demand (D):

“The neurotic, whether hysteric, obsessive, or, more radically, phobic, is the one who identifies the Other’s lack with the Other’s demand, with D. Consequently, the Other’s demand takes on the function of the object in the neurotic’s fantasy – that is, his fantasy is reduced to the drive: ($<>D).” (Lacan 2002[1996]-c: p698)

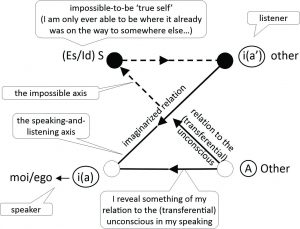

Second, this framing of the question only distinguishes an imaginarized relation to the little-o other from the relation to the big-O Other of the transferential unconscious (i.e., the two axes of the figure below). What is missing is the relation of the big-Other to the radically unconscious lack of the big Other S(A-bar). The challenge is in distinguishing a quadripod knotting the dynamic relations between a chthonic and neural radically unconscious Real with a radically unconscious Symbolic and Imaginary, a knotting that is structurally distinct from

- an autonoetic consciousness and what it can access in the preconscious, through which we identify agency in our world.

- a noetic transferential/repressed unconscious that object-relations theory characterizes so well, through which we relate to the objects in our world. It is our relation to the noetic small-s symbolic that puts us in relation to a big-O Other through its transferential effects.

- a relation to a chthonic and neural radically unconscious, the inclusion of which is a key characteristic of Lacan’s re-reading of Freud, our relation to which we experience in terms of the drive’s objets petit a through which we encounter our manque à être.

I find it helps to think of the relations between these three in terms of a Borromean knotting, each implicating the other two in the way it is taken up.[4]

Figure 1: Schema L from The Seminar on “The Purloined Letter” (Lacan 2002[1996]-b: p40[53])

No sense can be made of ‘the affirmation of being in relation to an originating loss’ without a way of reading Freud that holds this radically unconscious as structurally distinct. The relation to a radically unconscious Real is in the form of a relation to the necessary-Real of drive structuration as distinct from a Real-impossible that “never ceases not to be written” i.e., what never ceases to be written is the exogenous and endogenous excitation of the chthonic and radically unconscious neural networks.

Notes

[1] Here is what I wrote about Antigone’s relation to Creon’s decree in terms of ‘living between two deaths’, the first death being of any taken-for-granted definition of ‘the good’ (such as Creon’s), the second being ‘death-actual’ (Boxer 1994). The “other axis” is the ‘impossible axis’ in Figure 1.

“Lacan used the position of Antigone between-two-deaths as indicative of this ‘ethical’ position in relation to an Other law. Antigone is the heroine. She’s the one who shows the way of the gods. Creon exists to illustrate a function that Lacan showed was inherent in the structure of the ethic of tragedy, which was also that of psychoanalysis; Creon seeks the good. Something that is after all his role. The leader is he who leads the community. He exists to promote the good of all (Lacan 1992 [1959-1960]: p258). The reaction of Ismene – Antigone’s sister – is to argue for a compromise, pointing out that “really, given our situation, we don’t have much room to maneuver, so let’s not make things worse.” Antigone is unyielding. “Do you realize what is happening?” she asks. “Here’s the situation. This is what Creon has proclaimed for you and me. I speak for me. I am going to bury my brother.” Creon punishes her for breaking his law by having her buried alive.

Lacan elaborated two dimensions here: on the one hand the chthonic laws of the earth and, on the other, the commandments of the gods. Creon represents the laws of the city and identifies them with the decrees of the gods. Antigone, in resisting Creon’s orders is invoking the most radically chthonian of relations – blood relations – she is in a position to put the word of the gods on her side against the position taken by Creon. She puts her own being on the line for this being of the gods. Her desire becomes the desire of the big Other. But this takes a very particular form assumed by her in a very particular way – she speaks for herself alone in this.

This assumption of what the gods will is not an easy way if the will of the gods cannot be assumed through the good of the Law – it has to be looked for somewhere else.

So for Lacan, between-two-deaths is a being-in-relation-to this limit/impossibility which, in being true to desire, is also a giving up of the ‘good’ of the other axis.“

[2] Note that this is the 3rd moment to conclude preceding the 3rd crisis in which the question is “must I pay with my being”?

[3] In not giving up on one’s desire, therefore, one must pay with one’s being. This is the ethic of psychoanalysis, in which one must pay in three ways: with one’s time, with one’s words and with one’s being .

“Assuredly a psychoanalyst directs the treatment (…) in the capital outlay involved in the common enterprise, the patient is not alone in finding it difficult to pay his share. The analyst too must pay: pay with words no doubt, if the transmutation they undergo due to the analytic operation raises them to the level of their effect as interpretation. But also pay with his person in that, whether he likes it or not, he lends it as a prop for the singular phenomena analysis discovered in transference. Can anyone forget that he must pay for becoming enmeshed in an action that goes right to the core of being (Kern unseres Wesens), as Freud put it with what is essential in his most intimate judgment: could he alone remain on the sidelines? “ (Lacan 2002[1996]-a: pp490-1[587])

[4] Hence the primary forms of privation (real lack of a symbolic object by an imaginary agent) , frustration (imaginary lack of a real object by a symbolic agent) and castration (symbolic lack of an imaginary object by a real agent) (Lacan 2021[1956-57]: p261). Lacan gave up on elaborating these into the full set of six (Lacan 2016[2005]: pp178-9). Had he done so, he would have needed to include their perverse forms: the ‘say-everything’, the ‘impossible-to-say’ and the ‘no-thing-to-be-said’.

References

Boxer, P.J. 1994. ‘The Ethics of Psychoanalysis’, Journal of the Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research, 3: 73-87.

Lacan, J. 1992 [1959-1960]. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (Tavistock/Routledge: London).

———. 2002[1996]-a. ‘The Direction of the Treatment and the Principles of Its Power.’ in, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English (W.W. Norton & Co: New York).

———. 2002[1996]-b. ‘Seminar on “The Purloined Letter”.’ in, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English (W.W. Norton & Co: New York).

———. 2002[1996]-c. ‘The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious.’ in, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English (W.W. Norton & Company: New York).

———. 2016[2005]. Jacques Lacan: The Sinthome. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Boox XXIII 1975-1976 (Polity: Cambridge, UK).

———. 2021[1956-57]. Book IV – The Object Relation 1956-57 (Polity: Cambridge).